The Long Game: How LLMs are making human perseverance the ultimate scarce resource - Part 1

Beyond the Attention Economy: Why AI Will Make Long-Term Thinking Our Scarcest Asset

This is the first in a potentially 3-part series that delves into how the attention economy will move to its next phase: what I call the "perseverance" economy.

In this first piece, I'll show how throughout history, economies have been defined by their scarcest resources. While attention will continue to remain scarce today and in the near-medium term, I believe an even rarer trait is emerging: the human ability to work on complex problems over extended periods (5-10 years). This is especially true as LLMs provide instant answers to our questions.

Part 2 will explore why developing the skills to thrive in this perseverance economy is challenging due to two key paradoxes: the LLM paradox and the intelligence paradox.

The final piece will share tools and practices I've found helpful so far in overcoming these challenges.

P.S - All my essays are meant to be read end to end. I do not embed hyperlinks in the body of my essays, because as Nicholas Carr observed i strongly believe hyperlinks butcher our attention. If you are curious to know more, you can refer to the notes section which contains links to all the pieces I reference in my article.

Economies are defined by "scarcity"

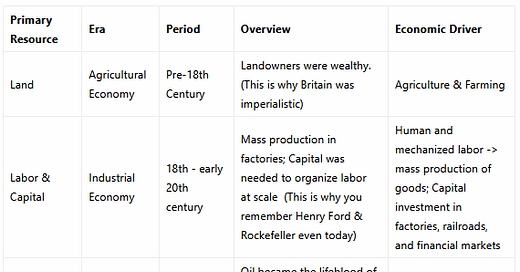

Every era of human existence is defined and shaped by the scarce resource that drives the economic system. Below is a brief overview:

Attention Economy:

My favorite definition of the attention economy comes from Baby George, a professor who says it is

A system where the ability to capture, direct, and retain human attention serves as the primary scarce resource and driver of value, superseding traditional factors of production in importance

The unique characteristic of the attention economy is the subjective perception of value. In all preceding economies, the primary resource could be measured objectively.

As Tara McMullin observes, "What you bought was valuable to you because your attention on the person selling the thing made it valuable." Given the subjectivity of attention and because it is in scarce supply and high demand, there are 3 keys to thriving:

Capturing the attention of a viable audience

Stewarding it into desirable actions (purchases, ad revenue, etc.)

Retaining it long-term

The term "attention economy" was popularized by Michael Goldhaber in his 1997 Wired article "Attention Shoppers," but it originated with Herbert Simon. In 1971, Simon penned what would become the defining quote of our digital age: "A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention" in his essay "Designing Organizations For An Information-Rich World."

One of the most fascinating takeaways from the Herbert Simon paper is his insight about the hidden cost of information consumption. Will Rinehart explains this brilliantly in his piece on the history of attention economy:

By spending an hour reading the newspaper, he would say to them, you give up the ability to work another hour and make another hour's worth of a wage. The opportunity cost is every hour you don't work.

Let's say that one of his friends made $100k a year and worked 37.5 hours a week. In this case, the hourly wage comes to $51.28. Reading the newspaper is time spent not working. So just over 45 minutes a day reading the newspaper comes to about $40 when the opportunity cost of wages is added.

That Sunday New York Times doesn't just cost $5 for the hardcopy, he would tell them. It costs you $45.

Rinehart extends this same logic to today's social media and reveals the staggering cost of our digital attention:

Users spend about 40 minutes per day on the site. (243 hrs / year); Average hourly wage earnings were $32.08 per hour in June 2022; The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy-wide marginal tax rate on labor income at 28.3 percent.

Roughly speaking then, the 2022 after-tax average wage rate stands at $23 per hour. This rate offers a rough estimate of the average value of an hour on social media.

Forty minutes a day for an entire year comes to a total value of TikTok of $5,596.66.

By way of reference, a couple of years back I ran through the numbers for Facebook and found that its value was $4,886.56 for the average user.

I did this analysis for myself and it is shocking. If every hour of my time is worth “x” then it helps me be more judicious of how I use my time every day.

Here is my first nudge for you: Try this yourself: calculate your hourly rate and multiply by your daily scroll / social media time. The number might not be huge, but it will just change how you spend tomorrow. (It did it for me.)

I recognize that not everyone will resonate with this economic framing of time. Time doesn't inherently come with a price tag. Time well spent with my daughter today is worth more than a million dollars I might earn once she turns 10 and naturally gravitates more toward her friends. And as Jenny Odell beautifully points out in her book "How to do Nothing," there's no virtue in mindless productivity in a world that has become a victim of context collapse, both spatially and temporally. When we don't make time for maintenance and repair—of relationships, communities, and ourselves—productivity metrics become meaningless.

In spite of these important counterpoints, I find that quantifying the monetary value of attention creates a tangible impact on my decision-making. My brain, shaped by experiences with scarcity and frugality, responds to these calculations in ways that help me be more intentional with my time. It has almost the same impact as Sam Harris’ pithy new year message on the Waking Up app, “the motto that guides me in every endeavor this year is the assumption that this will be the last year of my life”.

At a broader level, the attention economy has transformed how power operates in society. Companies and governments have built "information condensers" like Google Search, Spotify, or social media feeds that filter what we see and don't see.

This has given rise to what we might call "attention politics" – where controlling information flows means controlling influence. It's no coincidence that Elon Musk acquired Twitter, or that media outlets worldwide are being purchased by the ultra-wealthy. These aren't just business decisions; they're attempts to control the scarcest resource of our time.

How will LLMs disrupt value creation in the attention economy?

A Quick Historical Detour:

History doesn't just repeat—it rhymes in ways that should serve as warnings. Yet we often miss these harmonies until we're already caught in their chorus.

I often keep coming back to this anecdote that I read about the impact of modern appliances invented in the mid 20th century on housewives, which Oliver Burkeman points out in his book 4000 weeks.

These labor-saving appliances (microwave ovens, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and dishwashers) promised to liberate women from domestic drudgery, creating more time for leisure and self-fulfillment. Instead, they merely raised the bar of domestic expectations. Homes needed to be cleaner, meals more elaborate, and standards of housekeeping more exacting than ever before. The promised freedom evaporated into a new set of obligations.

Today, we stand at a similar inflection point with Large Language Models (LLMs). These AI tools promise to augment our cognitive capabilities and free us from mental labor. But just as the vacuum cleaner didn't actually create more leisure time, LLMs might not deliver the intellectual liberation we imagine.

Instead, they could raise the bar for human cognitive performance while simultaneously atrophying our cognitive abilities—unless we approach them with intention, curiosity and sustained attention.

While the trinity of internet, smartphone and social media has already challenged our capacity for deep thought and sustained attention, LLMs threaten to further erode our cognitive muscles as we have already let them become crutches rather than tools. Paul Graham alluded to this in his recent post Write and Writenots.

The real danger isn't that AI will replace us, but that we'll forget how to think and write without it. This combined loss of sustained attention, contemplation, and writing capabilities—the foundational elements of emotional intelligence and meaningful human endeavor—creates a dangerous possibility. We risk becoming mere prompt engineers of our own lives, outsourcing our deepest thinking to algorithms that can simulate reasoning but cannot truly understand.

This scary anecdote from Greg Isenberg (hat tip to my good friend Zeyad Mehran), sums it up well:

When Machines Think Cheaply: The Rising Premium on Emotional Wisdom

Large Language Models are poised to fundamentally transform the attention economy in ways more profound than smartphones or social media ever did. They don't just capture our attention—they threaten to reshape how we think, work, and create meaning.

As Karim Lakhani, the Harvard AI maven pointed out in his podcast with HBR, the internet lowered the cost of information transmission and led to the development of companies like Amazon, Google, etc., The biggest fallout of Gen AI, according to him is the drastic reduction in the cost of cognition, which has significant ramifications.

When AI can instantly generate passable content, research, code, and analysis, the cost of cognition plummets. This creates a paradoxical effect. As basic cognitive tasks become automated and frictionless, two things happen simultaneously:

Content production explodes as barriers to entry collapse (a LinkedIn influencer friend of mine stopped writing on the platform after LinkedIn was flooded with LLM-generated posts)

The perceived value of basic cognitive skills decreases

This leads us to the first major consequence: emotional intelligence becomes relatively more valuable as cognitive intelligence becomes commoditized.

The ability to ask the right questions, to determine what's worth thinking about, becomes more crucial than the mechanical aspects of thinking itself.

But there's a trap here. Emotional and cognitive intelligence aren't separate systems—they're interdependent. Think of them as a ship: emotional intelligence is the sail providing direction and motivation, while cognitive intelligence is the rudder ensuring we stay on course. When one atrophies, the entire vessel suffers.

AI Agents: The New Gatekeepers of Your Mind

As content proliferation accelerates, our attention becomes even more precious. As Kevin Kelly points out in his “The Future of Attention Economy” talk, while the monetary value of our attention/hour in 2019 was around $2-3USD, this will increase significantly. This is the rate that television and even websites (eg: YouTube) are charging advertisers for our attention.

Soon, we'll deploy AI agents as cognitive bodyguards—algorithmic filters on steroids that protect our attention from unwanted intrusions. These agents will make today's recommendation algorithms look primitive by comparison. In the AI-filtered future, that same hour might command $40-60. And in the next 10-15 years (if we are still alive then), Goldhaber’s prediction will come true. Attention will replace money as the primary currency of the world.

The consequence? Trust becomes the ultimate currency. When AI can filter almost everything, getting through to someone means being in their "trust circle." This explains why Nike recently partnered with Kim Kardashian—celebrities and influencers who've built trust become the gatekeepers to audience attention.

The filter bubble evolution represents a critical inflection point in how LLMs will reshape our attention landscape. This could unfold in two dramatically different ways:

In the optimistic scenario, AI agents could become tools for intellectual expansion rather than limitation. As the intelligence curve shifts right, these systems might introduce us to genuinely diverse perspectives, gradually dismantling our filter bubbles. We would develop a more nuanced grasp of complex realities, and perhaps even regain the capacity for shared understanding that seems increasingly rare—election results would no longer blindside half the population.

But the darker path seems equally plausible. LLMs, optimized for engagement rather than enlightenment, will perfect the art of reinforcing our existing beliefs while creating the illusion of intellectual exploration. Our filter bubbles wouldn't just persist—they would calcify, becoming impenetrable to contradictory evidence. Polarization would intensify as we lose not just the will but the cognitive and emotional capacity to understand those with different viewpoints.

The determining factor? Our collective ability to maintain attention on this problem long enough to solve it—exactly the capacity that's becoming most endangered.

Welcome to the Perseverance Economy

As filter bubbles evolve and AI agents mediate more of our information intake, we're facing not just a crisis of attention but a fundamental shift in our relationship with cognitive effort itself.

In this new landscape, a profound inversion occurs: when LLMs can generate instant answers to virtually any question, what becomes truly scarce isn't just attention, but something far more fundamental—perseverance. The capacity to work on complex problems for extended periods despite constant distraction may become the most valuable human trait in an AI-saturated world.

Consider my own experience: Before learning that i was a neuro-divergent in August 2023, I jumped from podcast to podcast weekly, went from one shiny new book to another every month, and never had any clue in what i wanted to do with my life even after being a self help addict for 20+ years. Post this revelation, as I've focused consistently on understanding attention better, I've discovered something profound: meaning and clarity emerges from perseverance, not the other way around.

When AI provides instant answers, our capacity for sustained focus disappears and perseverance atrophies. Yet the most significant human achievements—from Nobel Prize-winning research to artistic masterpieces—require decades of persistent effort.

As Annie Dillard reminds us, "How we spend our days is how we spend our lives." If we spend our days seeking instant solutions from LLMs, we lose the ability to work on problems that require years of dedication.

Here's another simple example: my experience writing this very article. I started with plans to write a primer on the attention economy, sparked by reading Jenny Odell's "How to Do Nothing?". This led me to James Williams' "Stand Out of My Light," and several other online rabbitholes, which utlimately made me realize that merely rehashing the attention economy wouldn't suffice—what's truly relevant is how LLMs will transform it.

As I researched, each concept branched into new territories: the LLM paradox, the intelligence paradox (cognitive versus emotional), professions worthy of value creation, history of attention economy, Herbert Simon's pioneering work... Each thread promising depth and insight, each tempting me down its own rabbit hole. What began as a focused essay became a sprawling three-part series as I struggled to contain the scope.

Do you see my challenge? I couldn't persevere even for a single article. The information overload combined with LLMs' capacity to instantly expand any concept creates an endless maze of fascinating tangents. It's exactly this tendency—the inability to maintain focus on a single problem long enough to reach meaningful depth—that illustrates why the next phase will be the "perseverance economy."

This is why I believe the next economic era will be the Perseverance Economy, where the scarcest resource isn't just attention, but the ability to maintain attention on meaningful problems over extended periods. In a world of constant distraction and instant gratification, those who can commit to play the long game will create disproportionate value.

In Part 2 of this series, I'll explore why developing this capacity for perseverance is particularly challenging due to two key paradoxes: the LLM paradox and the intelligence paradox.

Until then, I invite you to consider: what problem would you work on if you could maintain focus for a decade? And what keeps you from starting that journey today?

Notes:

1997 Wired article "Attention Shoppers" by Michael Goldhaber

1971 Paper titled "Designing Organizations For An Information-Rich World" by Herbert Simon

2022 Substack piece "The attention economy: a history of the term, its economics, its value, and how it is changing politics" by Will Rinehart

The Future of Attention Economy, Kevin Kelly - 2019 (Transcript)

AI Won't Replace Humans—But Humans With AI Will Replace Humans Without AI, Karim Lakhani’s appearance on the HBR podcast, 2023

Definitely, it's sort of considered difficult or time-consuming to solve complex problems nowadays.

It's more of quicker work for quicker gains. What we aren't realising is that AI companies are building in the concept of quicker productivity in humans so high that we may lose the quality. Someone is considered slow and less competent just if they take more time to understand and to give in their best work.

Sounds a lot like we need Gyms for the Brain the way our bodies need gyms to function properly.

I love the question of 'what is scarce today?' and I suspect it's not just attention but also trust.

With the ability to mass produce content garbage, customers and clients have license to be more suspicious and wary of people's work